N.B.: I am still completing this post.

When I was getting interviewed for my admission, Ms. Lenka Karkoskova (DipTESOL Lead) asked me what my favorite area of improvement was. Before you can say Jack Robinson, I said, “Phonology!”

Why? Because I am from a region in India where phonology teaching is nonexistent. I am from Punjab. We don’t have language schools, and I have not worked for any to date.

However, I wanted to be a better teacher. I want to be a better teacher. I will want to be a better teacher. Is that possible without knowing how to teach pronunciation?

For instance, a majority of my students prepare for IELTS. The Speaking score here relies 25% on pronunciation. Need I say more?

I think I worked hard, and I ended up getting 77%. One needs 80% for a Distinction. Ouch! I know, right? I know it’s not a very high score. However, I am so happy that I have been able to get so much. Thanks a lot to my phonology tutor, Mr. Mark Lewis. He is so knowledgeable and helpful. I am equally thankful to the best mentor I have gotten in my life, that is, Ms. Karkoskova. She tirelessly helped me up my phonology game throughout the course. I am sure I am not the best student Mr. Lewis and Ms. Karkoskova got. However, I couldn’t have gotten better phonology guides.

(Wait. Wiping the 77 tears off my face!)

(I am ready again.)

So, What Did I Do?

Let’s Start with the Materials:

YouTube:

I am in love with Geoff Lindsey’s YouTube channel. Oh, my God! The man is a wizard. The channel has in-depth analyses of various concepts needed for one’s growth as a pronunciation teacher, and the videos are fun.

However, if you are a neophyte as I was (Now, I can assimilate and elide stuff, so “was” instead of “is”), I think a better starting channel would perhaps be Billie English. It was the channel that I started watching when I first started studying phonology well. Billie has explained so many concepts so patiently that I call myself a fan of her work.

The Adrian Underhill videos on Macmillan Education ELT are terrific, too, and so are Emma’s on Pronunciation with Emma. Moreover, there is a channel called Basic American Pronunciation with Diane. The lady is a treasure trove of knowledge. Finally, Tim’s Pronunciation Workshops are crisp and have the va-va-voom.

Books:

Clement Laroy’s Pronunciation helped me treat some students’ linguistic jingoism.

Gerald Kelly’s How to Teach Pronunciation helped me know the basics.

Pamela Rogerson-Revell’s English Phonology and Pronunciation Teaching helped me take the basics further.

Adrian Underhill’s Sound Foundations helped me teach pronunciation.

Of course, all the books helped me with each area. However, the mentioned features were their highlights in my case.

Finally, the free PronPack resources by Mark Hancock are better than porn. Use them to know what I mean, and thank me later.

The Topics I Worked On:

No surprises here!

The sounds. Word stress. Sentence stress. Intonation. Connected speech features, like catenation, intrusion, assimilation, and so on.

I studied translanguaging quite a lot because I used it a lot in my classes. Two personalities who were my go-to translanguaging savants were Ofelia García and Jim Cummins. Further, I did study some phonological analyses comparing Hindi (my students’ L1 in general) and English.

The crux is that the deeper you dig, the sweeter the fig.

How Did the Exam Go?

Section 1: The Presentation and the Related Discussion

I chose a translanguaging-based real lesson of mine. This is because real-use references are necessary. Also, I made use of quotes by Cummins, García, and Lindsey.

I talked about what contractions are, what their general types are, why I chose translanguaging, how I used it to teach the auxiliary contractions, and what my evaluation methods were.

The Activity:

The follow-up questions (probably) were:

1. Why do students need to be able to use contractions? (In my case, I referred to the PTE score needs. Also, general fluency was referred to.)

2. Are contractions more important orally or aurally? (I said, “Both.” Only robots wouldn’t use contractions. Thus, they are important if you want to sound natural in a conversation while understanding the other participant who sounds natural. I referred to some corpus findings here as well.)

3. What problems do contractions pose to learners? (Negative ones are stressed, but positive ones are weak. For example, “can’t” sounds like “can,” and “can” becomes /kən/. Multiple meanings in cases like “they’d” and “he’s.” In my case of Punjabi students, there is no practice in schools; thus, the learners have to be made accustomed to them.)

4. Why did I use Hindi? (I relied on the learners’ established schemas. I referred to the cognitive load theory for this point. Also, the activity was for my PTE students. Such exam candidates I get want to pass their exams as soon as possible. Thus, relying on what they know was better than teaching them the phonemic symbols first. Next, Hindi is largely a phonetic language, so you speak what you see. Finally, most of the English sounds are there in Hindi. Even aspiration is there.)

5. Is it right to use learners’ L1(s) when teaching them English? (Jim Cummins says languages can feed off each other, and we get positive results if we make use of this reality. My activity did bring about such results. Ofelia García says a multilingual learner has to have a unitary language system rather than a first language, a second language, and so on. Also, my activity had the pronunciations written in Hindi; it did not have the meanings in that language. Plus, I made sure only one contraction of each type was taught using translanguaging. The subsequent ones relied on Piaget’s assimilation. Moreover, this was only the first contraction lesson. I did not need translanguaging in the subsequent classes focusing on negative contractions, double contractions, and so on.)

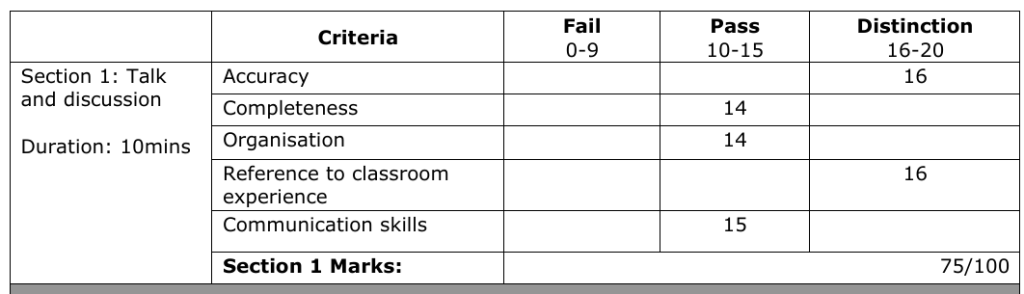

This is what I got:

Accuracy: I think I should have studied more.

Completeness: I think I should have practiced more. Also, I think I should have explained what translanguaging is in the presentation.

Organization: I think a couple of mocks by OIDI would have helped me.

Reference to Classroom Experience: I think I should have thought about it more.

Communication Skills: I think this area suffered owing to the Unit 4 tiredness because that unit had ended only a day before. Unit 4 is a purgatory. Also, since I very rarely get to talk to an erudite person like Mr. David Young, I tend to get overexcited when I get such a chance. Hence, my speech suffers.

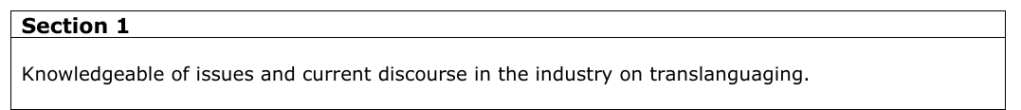

Examiner’s Comments:

I agree. 💅.

Section 2: The Transcription

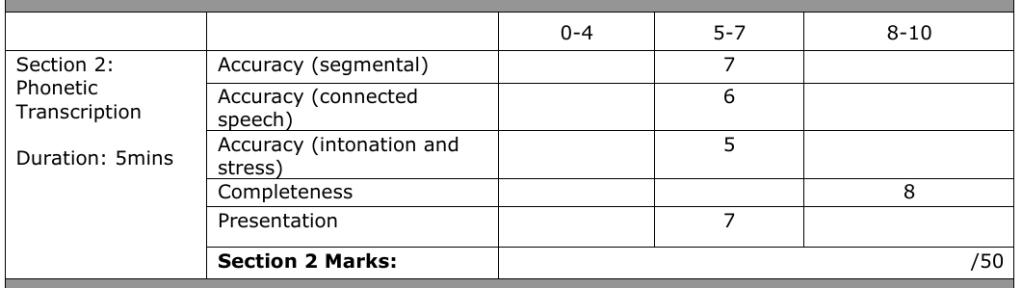

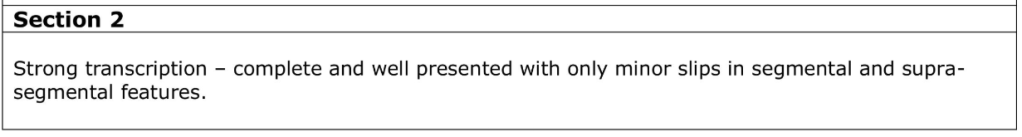

There are no practice materials anywhere. However much I could practice, I did. The result was bad.

The total is 33. Maybe a clerical error.

Try to find some materials and practice as much as you can. At the time of the exam, the 5-minute duration gets completed before you know it. You tend to forget the symbols and the requirements if you are a noob like me. (Yes, “are.” I think I still am a noob.)

I think the utterance was something like the following:

Are you having a laugh?

I’ve told you this many times! No pineapple on pizzas!

Sometime before, I had asked Billie English to evaluate a transcript written by me. It may help you.

Here it is:

Section 3: The Long Discussion

It was so cool that it made me academically horny. We talked about so many things.

The answers that I remember are, expectedly, unlikely to be the same as the exam answers. However, they may give you an idea of decent responses because . . .

I will keep updating the list. The main thing to remember is to use theory, quotes, and your real classroom examples in a coherent manner.

1. How do you teach pronunciation in your classes?

Answer: My classes have pronunciation segments that are 5 to 10 minutes long. I choose an aspect that complements the topic at hand. For example, in a grammar class focusing on the third conditional, I teach triple contractions like “I’d’ve” and “you’d’ve.” Similarly, if it’s a vocabulary class, I use drilling to help my learners with more than one aspect. For example, I recently taught the word “pushover.” After the word stress drilling using only the word, I used the sentence “Rachel’s a pushover.” It has a contraction. Moreover, we could work on sentence stress and intonation as well.

2. Why was sentence stress important?

Answer: Stress shifting (or iambic reversal) can happen when words are used in chunks. For example, in “Piccadilly,” “dilly” carries the main stress, but that’s not the case in “Piccadilly Circus” because “cir” is generally the tonic syllable.

3. Do you think pronunciation teaching has something to do with reading?

Answer: Yes! The PTE has a category called Read Aloud. The candidates are supposed to read a text aloud. If I, for example, don’t teach the pronunciation of “tomb” beforehand, most of my students are very likely to use /tɒmb/ instead of /tuːm/. Also, to get a high score, candidates are supposed to employ elision, assimilation, and so on. Moreover, knowing about catenation makes their speech smoother.

4. What about pronunciation in a listening lesson?

Answer: The students need logical reasons for “lauren order” (“law and order”) or “hambag” (“handbag”) when they have heard the former but the answer key has the latter (the one in parentheses). I tend to make them hear such things to excite them, and then I reveal the connected speech feature(s).

5. What about when you use authentic materials?

Answer: It’s quite similar to what coursebooks do. For the pronunciation stage, edit the video or the audio a little to highlight the pronunciation elements. For example, I remember a F.R.I.E.N.D.S scene in which Phoebe repeatedly uses the weak form of “was.” It is very useful when it comes to introducing the weak form. I can say this at least to my demographic. They have, most of the time, heard only /wɒz/.

6. Why do some teachers hesitate to teach intonation?

Answer: Probably because we know it only mentally, but we have to teach it practically. Owing to this, I am currently interested in ToBI. I watched Peter Roach’s video on it, and perhaps it could provide me with something more concrete than saying, “The voice goes up.” Also, I think sometimes rules defeat us. A rising intonation pattern is perhaps not always for confirming something.

7. How should a new teacher start teaching intonation?

Answer: I think Adrian Underhill’s book called Sound Foundations mentions different perspectives on intonation that can be useful here. First, to keep it easy for themself (and perhaps the students), the rule-bound grammatical basis is great. For example, an open-ended question has to have a falling intonation pattern, and a yes/no question has to have a rising one. These are indeed the general patterns. When the rules have occupied some space in the teacher’s brain, the teacher will be irked by the anomalies. For example, they may hear a clerk say, “What is your name?” with a rising intonation pattern on “name” because a customer is not telling their name. After such a case and similar ones, the teacher’s grammar–intonation schemas will probably be modified, and their understanding will be deepened. They will understand the idea that intonation is, by and large, about one’s attitude or intentions. Then, the teacher will become more confident regarding teaching intonation, and they will themself say, “These rules can have exceptions based on the mood of the person.” The teacher will also have become more adept at teaching intonation in continued discourse instead of individual sentences in the meantime.

Well done on an excellent mark in the exam. I know you mentioned that 77% is not a very high score, but it really is. 100% is not and never can be the target – this is a different kind of exam to a formative achievement test from school, it’s a proficiency test which demonstrates your overall knowledge, and you’ve done that admirably. You’ve also written a post which will be helpful for future candidates preparing for the DipTESOL Unit 3 exam. Good luck with the rest of your Dip!

Sandy

LikeLike